Some early Japanese visitors to Tibet

བོད་དང་ཉི་འོང་དབར་སྔ་མོའི་འབྲེལ་བ།

On the 121st anniversary of Rev Kawaguchi Ekai's reaching Tibet (the actual date: 4/07/1900), I reproduce below the notes I shared with the visiting Japanese university students in Dharamsala in 2004 at Tibet Museum.

My respect and appreciation is with the Japanese who visited Tibet in those difficult times. They lived with the Tibetans and later told our true story. If possible, I would like to pay respect to the families of these devoted, adventurous, and brave souls.

The talk note is here below:

Like many foreigners, Japanese also took interest in Tibet, and they ventured into the land in the late 19th and early 20th century. Tibet remained in self isolation with a view to preserve its own religious faith, culture, and language. Tibet remained oblivious to the world wars and the impending danger from the aggressive neighbor in the east, China.

It is recorded that some ten Japanese visited Tibet with different objects and motives at same and different times when Tibet was an independent nation. Some have seen the last days of Tibetan independence. Their writings and memoirs have become proof of Tibetan independence. They are known as Nyuzosha, one who had entered Tibet, in Japanese. Here is the brief notes on those determined Japanese and the purpose of their visit, and what they did in Tibet.

1900: Kawaguchi Ekai (1866-1945), a student of Sarat Chandra Das, visited Tibet disguised as a Chinese monk. He entered Tibet in 1900 and reached Lhasa in March 1901. He was inspired to study original translation of Buddha`s teaching. He studied in Sera monastery, one of the largest monasteries in Tibet. As he helped the local with his medical knowledge, he was also known as Sera Amchi. He is said to have informed Sarat Chandra Das about the Russian influence in Tibet that triggered Young Husband expedition of 1904. He returned in 1903. His book, "Three Years in Tibet", Chibeto Ryokoki, became very popular. He visited Tibet again in 1913-1915.

1901: Narita Yasutera (1864-1915), a Buddhist priest and student of Nanjo Bunyo reached Lhasa in Dec 1901. He was earlier with Imperial army, later sent to the USA on a mission, then to Taiwan. It was not clearly known why he was sent to Tibet. His dairy "Shin-Zo Nishi" records his travel in Tibet. Black Dragon Society (Kokuryukai) also has his record in "Senkoku Shinshi Kiden".

Around that time a priest by the name of Nomi Kan (1868-?), also a student of Nanjo Bunyo, tried entering Tibet. He reached upto Bathang and it is not clearly known of his fate thereafter.

1905: Teramoto Enga (1872-1940), a Buddhist priest, stayed briefly in Tibet and later continued to Peking. But his influence over Japanese – Tibetan relationship was considered substantial. He sent information to the Japanese government, Nishi Hongwanji Temple. In 1903, Count Otani Kozui was the head of the Hongwanji Temple. He had his brother Sonya Otani meet the 13th Dalai Lama at Wutaishen and planned student exchange and the visit of His Holiness the 13th Dalai Lama to Japan.

1910: Yajima Yasujiro (1882-1963), a Russo-Japan war (1904-05) veteran. British took him for a spy. He stayed in Tibet briefly then left. He visited again in 1912 disguised as a coolie and stayed in Tibet till 1918. He drew a map and was later given charge of one section of the Tibetan army, which he trained in Japanese method of warfare. His Holiness the 13th Dalai Lama was said to have been fond of him. He married with a Tibetan woman, bore a child Ishin. The boy later died in a war with China.

1912: Aoki Bunkyo (1886-1956), representative of Count Otani of Nishi Hongwanji, stayed in Tibet till 1916. Although a priest, his activities were mostly secular. It is said the idea of pan-Buddhism, pan-Asianism, and a Buddhist renaissance was dear to the nationalist Japanese. Count Otani was in favor of this idea. Aoki translated Japanese infantry manual into Tibetan, unfortunately, a copy could not be found. He is said to be in a committee who designed Tibetan flag. He was sent to buy arms (guns) for Tibetan government.

1913: Tada Tokan (1890-1967), also a representative of Count Otani, but he confined himself to the study of Buddhism and was very critical of Aoki Bukyo's activities. He stayed in Tibet for ten to eleven years. Both Aoki and Tada were said to have been invited by the Dalai Lama as result of the Dalai Lama`s meeting with Count Otani at Peking in 1908. Count Otani was said to have fallen from power in 1914. Tada wrote "Dalai Lama Jusanse" and "Chibtto Taizaiki". H.H. the 13th Dalai Lama continued correspondence with him with a hope that the Japanese government would help Tibet in checking Chinese aggressions.

1939: Kimura Hisao (Dawa Sangpo) (1922-1989), a spy disguised as Mongolian stayed in Tibet for more than a year. Around that time another spy, Nishikawa Kazumi (1918-2008) also visited Tibet. But it is said that they were so lost in the way that they reached Tibet only after the war. Kimura's story is in "Japanese Agent in Tibet" and Nishikawa's story is in "The Rising Sun in the land of Snow", both by Scott Berry.

1939: Nomoto Jinzo (1917-2014), a Japanese spy, wrote "Chibetto Senko". He was in Tibet on information gathering mission. He entered Tibet in 1939.

Above information was compiled for a talk given to a visiting Japanese University Students at the request of the Department of Information (DIIR), May 2004 / updated 17/02/2022

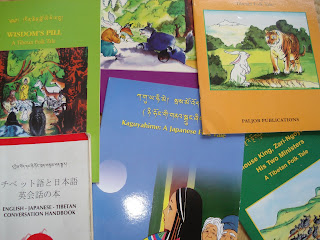

Related books and important years:

Three years in Tibet by Kawaguchi Ekai

Japanese agent in Tibet by Kimura Hisao and Scott Berry

Monks, Spies and a Soldier of Fortune: the Japanese in Tibet by Scott Berry

A stranger in Tibet: A Japanese zen monk by Scott Berry

Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thupten Gyatso (1876-1933) by Tada Tokan

Young Husband expedition to Tibet 1904

World War I (1914 - 1918) World War II (1939-1945)

+012.jpg)